Maginot Line

| Maginot Line | |

|---|---|

| Ligne Maginot | |

| Eastern France | |

The entrance to Ouvrage Schoenenbourg along the Maginot Line in Alsace |

|

| Type | Defensive line |

| Built | 1930–40 |

| Construction materials |

Concrete, steel |

| In use | 1935–69 |

| Controlled by | France |

| Battles/wars | Battle of France, World War II |

The Maginot Line (French: Ligne Maginot, IPA: [liɲ maʒino]), named after French Minister of Defense André Maginot, was a line of concrete fortifications, tank obstacles, artillery casemates, machine gun posts, and other defenses, which France constructed along its borders with Germany and Italy, in the light of experience from World War I, and in the run-up to World War II. Generally the term describes only the defenses facing Germany, while the term Alpine Line is used for the Franco-Italian defenses.

The French established the fortification to provide time for their army to mobilize in the event of attack and/or to entice Germany to attack neutral Belgium to avoid a direct assault on the line. The success of static, defensive combat in World War I was a key influence on French thinking. The fortification system successfully dissuaded a direct attack. However, it was strategically ineffective, as the Germans did indeed invade Belgium, flanked the Maginot Line, and proceeded relatively unobstructed.[1] It is a myth however that the Maginot Line ended at the Belgian border and was easy to circumvent.[2] The fortifications were connected to the Belgian fortification system, of which the strongest point was Fort Eben-Emael. The Germans broke through exactly at this fortified point with a unique assault that incorporated gliders and shaped explosive charges. The surrender of the fort, in less than two days, allowed the invasion of France.

Contents |

Planning and construction

The defenses were first proposed by Marshal Joffre. He was opposed by modernists such as Paul Reynaud and Charles de Gaulle who favoured investment in armour and aircraft. Joffre had support from Henri Philippe Pétain, and there were a number of reports and commissions organised by the government. It was André Maginot who finally convinced the government to invest in the scheme. Maginot was another veteran of World War I, who became the French Minister of Veteran Affairs and then Minister of War (1928–1931).

Part of the rationale for the Maginot line stemmed from the massive French losses during the First World War, and their effects on French demographics. The drop in the national birth rate during and after the war, resulting from a national shortage of young men created an "echo" effect in the generation that would provide the French conscript army in the mid-1930s. Faced with inadequate personnel resources, French planners had to rely more on older and less fit reservists, who also would take longer to mobilize. Static defensive positions were therefore intended not only to buy time, but also to defend an area with fewer and less mobile forces (although France deployed twice as many men in the Maginot Line than the Germans had in the opposing Heeresgruppe C).

The line was built in a number of phases from 1930 by the STG (Service Technique du Génie) overseen by CORF (Comission d'Organisation des Régions Fortifiées). The main construction was largely completed by 1939, at a cost of around 3 billion French francs.

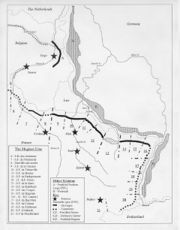

The line stretched from Switzerland to Luxembourg, although a much lighter extension was extended to the Strait of Dover after 1934. The original line construction did not cover the area chosen by the Germans for their first challenge, which was through the Ardennes in 1940, a plan known as Fall Gelb. The location of this attack, probably because of the Maginot line, was through the Belgian Ardennes forest (sector 4) which is off the map to the left of Maginot line sector 6 (as marked).

Purposes

The Maginot Line was built to fulfill several purposes:

- To avoid a surprise attack and to give alarm.

- To cover the mobilization of the French Army (which took between 2 and 3 weeks).

- To save manpower (France counted 39,000,000 inhabitants, Germany 70,000,000).

- To protect Alsace and Lorraine (returned to France in 1918) and their industrial basin.

- To be used as a basis for a counter-offensive.

- To push the enemy to circumvent it while passing by Switzerland or Belgium.

- To hold the enemy while the main army could be brought up to reinforce the line.

Organization

Although the name "Maginot Line" suggests a rather thin linear fortification, the Line was quite deep, varying in depth (i.e., from the border to the rear area) from between 20 to 25 kilometers. It was composed of an intricate system of strong points, fortifications, and military facilities such as border guard posts, communications centers, infantry shelters, barricades, artillery, machine gun, and anti-tank gun emplacements, supply depots, infrastructure facilities, observation posts, etc. These various structures reinforced a principal line of resistance, made up of the most heavily armed "ouvrages", which can be roughly translated as fortresses or major defensive works.

From the front and proceeding to the rear, the Line was composed of:

- Border Post line (1): This consisted of blockhouses and strong houses which were often camouflaged as inoffensive residential homes, built within a few metres of the border, and manned by troops so as to give alarm in the event of sneak or surprise attack as well as delay enemy tanks with prepared explosives and barricades.

- Outpost and Support Point line (2): Approximately 5 kilometres (~2.5-3 miles) behind the border, a line of anti-tank blockhouses were intended to provide resistance to armoured assault sufficient to delay the enemy so as to allow the crews of the "C.O.R.F. ouvrages" to be ready at their battle stations. These outposts covered major passages within the principal line.

- Principal line of resistance (3): This line began 10 kilometres (~6 miles) behind the border. It was preceded by anti-tank obstacles which were metal rails planted vertically in 6 rows with heights varying from 0.70 to 1.40 m (2-4 feet) and buried to a depth of two meters (6-7 feet). These anti-tank obstacles extended from end to end in front of the major works across hundreds of kilometres, interrupted only by extremely dense forests, rivers, or other nearly-impassable terrain.

- The anti-tank obstacle system was immediately followed by an anti-personnel obstacle system made primarily of very dense barbed wire. Anti-tank road barriers also made it possible to block roads at necessary points of passage through the tank obstacles.

- Infantry Casemates (4): These bunkers were armed with twin machine-guns (abbreviated as JM in French) and anti-tank guns of 37 or 47 mm. They could be single (with only one firing room in only one direction) or double (two firing rooms, in 2 opposite directions). These generally had 2 floors, with a firing level and a support/infrastructure level that provided the troops with rest and services (power generating units, reserves of water, fuel, food, ventilation equipment, etc.). The infantry casemates often had 1 or 2 "cloches" or turrets located on top of them. These GFM cloches sometimes were used to emplace machine guns or observation periscopes. Their crew was 20 to 30 men.

- Petits ouvrages (5): These small fortresses reinforced the line of infantry bunkers. The petits ouvrages were generally made up of several infantry bunkers connected by an underground tunnel network to which were attached various buried facilities, such as barracks, electric generators, ventilation systems, mess halls, infirmaries, and supply caches. Their crew consisted of between 100 and 200 men.

- Ouvrages (6): These fortresses were the most important fortifications on the Maginot Line, having the sturdiest construction and also the heaviest artillery. These were composed of at least six "forward bunker systems" or "combat blocks", as well as two entrances, and were interconnected via a network of underground tunnels that often featured narrow gauge electric railways for transport between bunker systems. The various blocks contained necessary infrastructure such as power stations with generating units, independent ventilating systems, barracks and mess halls, kitchens, water storage and distribution systems, hoists, ammunition stores, workshops, and stores of spare parts, food, etc. Their crews ranged from 500 to more than 1000 men.

- Observation Posts (7) were located on hills that provided a good view of the surrounding area. Their purpose was to locate the enemy and direct and correct the indirect fire of artillery from the artillery fortifications as well as to report on the progress and position of key enemy units. These are large reinforced buried concrete bunkers, equipped with armored turrets containing high-precision optics that were connected with the other fortifications by field telephone and wireless transmitters (known in French by the acronym T.S.F.).

- Telephone Network (8): This system connected every fortification in the Maginot Line, including bunkers, infantry and artillery fortresses, observation posts, and shelters. Two telephone wires were placed parallel to the line of fortifications, providing redundancy in the event of a wire getting cut. There were places along the cable where dismounted soldiers could connect to the network.

- Infantry Reserve Shelters (9): These were found between 500 and 1000 meters (~.3-.6 miles) behind of the principal line of resistance. These were buried concrete bunkers designed to house and shelter up to a company of infantry (200 to 250 men), and had such features as electric generators, ventilation systems, water supplies, kitchens and heating, which allowed their occupants to hold out in the event of an attack. They could also be used as a local headquarters and as a base from which to carry out counter-attacks.

- Flood Zones (10) were natural basins or rivers that could be flooded on demand and thus constitute an additional obstacle in the event of an enemy offensive.

- Safety Quarters (11) were built near the major fortifications in order to make it possible for fortress ("ouvrage") crews to reach their battle stations within the shortest possible time in the event of a surprise or sneak attack during peacetime.

- Supply depots (12).

- Ammunition dumps (13).

- 60 cm (~24 inch) Narrow Gauge Railway System (14): A network of narrow-gauge railways was built so as to rearm and resupply the major fortresses ("ouvrages") from supply depots up to 50 kilometers (35 miles) away. Gasoline-powered armored locomotives pulled supply trains along these narrow-gauge lines. (A similar system was developed with armored steam engines back in 1914-1918.)

- High-voltage Transmission Lines (15), initially above-ground but then buried, and connected to the civil power grid, provided electric power to the many fortifications and fortresses.

- Heavy rail artillery (16) was hauled in by locomotives to predesignated locations so as to support the pre-emplaced artillery located in the fortresses, which was intentionally limited in range to 10-12 kilometers.

Inventory

Ouvrages

There are 142 ouvrages, 352 casemates, 78 shelters, 17 observatories and around 5,000 blockhouses in the Maginot Line.[3]

Armoured cloches

There are several kinds of armoured cloches. The word cloche is a French term meaning bell due to its shape. All cloches were made in an alloy steel. Cloches are non-retractable turrets.

- The most widespread are the GFM cloches, where GFM means Guettor - Rifle machine-gun. They are composed of 3 to 4 openings, called crenels or embrasures. These crenels may be equipped as follows: Rifle machine-gun, direct vision block, binoculars block or 50mm mortar. Sometimes, the cloche is topped by a periscope. There are 1,118 GFM cloches on the Line. Almost every block, casemate and shelter is topped by one or two GFM cloches.

- The JM cloches are the same as the GFM cloches except that they have one opening equipped with a pair of machine-guns. There are 174 JM cloches on the Line.

- There are 72 AM cloches (mixed weapons) on the Line, equipped with a pair of machine guns and a 25mm anti-tank gun. Some GFM cloches were transformed into AM cloches in 1934. (The aforementioned total does not include these modified cloches.)

- There are 75 LG cloches (lance-grenade/grenade launcher) on the Line. Those cloches are almost completely covered by concrete, only a hole is kept open to launch the grenades.

- There are 20 VP cloches (periscopic vision) on the Line. These cloches could be equipped with several different periscopes. Like the LG cloches, they were almost completely covered by concrete.

- The VDP cloches (direct and periscopic vision) are similar to the VP cloches, but have two or three openings to provide a direct view. Consequently, they were not covered by concrete.

GFM cloche |

JM cloche |

AM cloche |

LG cloche |

VP cloche |

VDP cloche |

Retractable turrets

The Line included the following retractable turrets.

- 21 turrets of 75 mm model 1933

- 12 turrets of 75 mm model 1932

- 1 turret of 75 mm model 1905

- 17 turrets of 135 mm

- 21 turrets of 81 mm

- 12 turrets for mixed weapons (AM)

- 7 turrets for mixed weapons + mortar of 50 mm

- 61 turrets of machine-guns

|

75mm Turret model 1932 |

135mm Turret |

81mm Turret |

Machine-gun Turret |

AM (Mixed-Weapons) Turret |

Artillery

Anti-tank guns

Features

The specification of the defences was very high, with extensive and interconnected bunker complexes for thousands of men; there were 45 main forts (grands ouvrages) at 15 kilometres intervals, 97 smaller forts (petits ouvrages) and 352 casemates between, with over 100 kilometres of tunnels. Artillery was coordinated with protective measures to assure that one fort could support the next in line by bombarding it directly without harm. The largest guns were therefore 135mm fortress guns; larger weapons were to be part of the mobile forces and were to be deployed behind the lines.

The fortifications did not extend through the Ardennes Forest (which was believed to be impenetrable) or along France's border with Belgium, because the two countries had signed an alliance in 1920, by which the French army would operate in Belgium if the German forces invaded. When Belgium abrogated the treaty in 1936 and declared neutrality, the Maginot Line was quickly extended along the Franco-Belgian border, but not to the standard of the rest of the Line. As the water table in this region was high, there was the danger of underground passages getting flooded, which the designers of the line knew would be difficult and expensive to overcome.

There was a final flurry of construction in 1939–1940 with general improvements all along the Line. The final Line was strongest around the industrial regions of Metz, Lauter and Alsace, while other areas were in comparison only weakly guarded. In contrast, the propaganda about the line made it appear far greater a construction than it was; illustrations showed multiple stories of interwoven passages, and even underground railyards and cinemas. This reassured allied civilians.

Czech connection

Czechoslovakia also was in fear of Hitler and began building its own defenses. As an ally of France, they were able to get advice on the Maginot design and apply it to Czechoslovak border fortifications. The design of the casemates is similar to the ones found in the southern part of the Maginot Line, and photos of such are often confused with those of the Maginot. With the Munich Agreement the Germans were able to use the Czech fortifications to study and plan attacks that proved very successful against the western fortifications (Fort Eben-Emael is the best known example).

German invasion in World War II

The World War II German invasion plan of 1940 (Sichelschnitt) was designed to deal with the Line. A decoy force sat opposite the Line while a second Army Group cut through the Low Countries of Belgium and the Netherlands, as well as through the Ardennes Forest which lay north of the main French defences. Thus the Germans were able to avoid a direct assault on the Maginot Line by violating the neutrality of Belgium, Luxemburg and the Netherlands. Attacking on May 10, German forces were well into France within five days and they continued to advance until May 24, when they stopped near Dunkirk.

During the advance to the English Channel, the Germans overran France's border defense with Belgium and several Maginot Forts in the Maubeuge area, whilst the Luftwaffe simply flew over it. On May 19, the German 16th Army successfully captured petit ouvrage La Ferte (southeast of Sedan) after conducting a deliberate assault by combat engineers backed up by heavy artillery. The entire French crew of 107 soldiers was killed during the action. On June 14, 1940, the day Paris fell, the German 1st Army went over to the offensive in "Operation Tiger" and attacked the Maginot Line between St. Avold and Saarbrücken. The Germans then broke through the fortification line as defending French forces retreated southward. In the following days, infantry divisions of the 1st Army attacked fortifications on each side of the penetration; successfully capturing four petits ouvrages. The 1st Army also conducted two attacks against the Maginot Line further to the east in northern Alsace. One attack successfully broke through a weak section of the Line in the Vosges Mountains, but a second attack was stopped by the French defenders near Wissembourg. On 15 June, infantry divisions of the German 7th Army attacked across the Rhine River in Operation "Small Bear", penetrating the defenses and capturing the cities of Colmar and Strasbourg.

By early June the German forces had cut off the Line from the rest of France and the French government was making overtures for an armistice, which was signed on June 22 in Compiègne. As the Line was surrounded, the German Army attacked a few ouvrages from the rear, but were unsuccessful in capturing any significant fortifications. But the main fortifications of the Line were still mostly intact and manned with a number of commanders wanting to hold out; and the Italian advance had been successfully contained. Still, Maxime Weygand signed the surrender and the army was ordered out of their fortifications, to be taken to POW camps.

When the Allied forces invaded in June 1944 the Line, now held by German defenders, was again largely bypassed, with fighting only touching a part of the fortifications near Metz and in northern Alsace towards the end of 1944. At one point during the fighting, General Martin, commander of the IX Corps, was ordered to advance forward from the Maginot line against a German division, and thus locked the concrete bunkers and left the keys with a colleague. While his colleague's unit was ordered south to reinforce French cities, Martin was forced to retreat from his unsuccessful attack and found himself pursued by a German tank division, and locked out of his own fortifications. He was forced to employ French engineers and sappers to break into the bunkers, which were subsequently overrun by the Germans.[4]

After World War II

After the war the Line was re-manned by the French and underwent some modifications. With the rise of the French independent nuclear deterrent by 1960 the Line became an expensive anachronism. Some of the larger ouvrages were converted to command centers. However, when France withdrew from NATO's military component (in 1966) much of the Line was abandoned, with the NATO facilities turned back over to French forces and the rest of it auctioned to the public or left to decay.[5] Ouvrage Rochonvillers was retained by the French Army as a command center into the 1990s, but has recently been closed. Ouvrage Hochwald is the only facility in the main line that remains in active service, as a hardened command facility for the French Air Force known as Drachenbronn Air Base.

In 1968 when scouting locations for On Her Majesty's Secret Service, producer Harry Saltzman used his French contacts to agree to using portions of the Maginot Line as SPECTRE headquarters in the film. Saltzman provided art director Syd Cain with a tour of the complex but Cain said that not only would the location be a nightmare to light and film inside, but that artificial sets could be constructed at the studios for a fraction of the cost.[6] The idea was shelved.

See also

- List of all works on Maginot Line

- List of Alpine Line ouvrages

- Siegfried Line

- Atlantic Wall

- Czechoslovak border fortifications

Notes

- ↑ http://www.dushkin.com/text-data/articles/23427/23427.pdf

- ↑ Mosier, J. The Blitzkrieg Myth: How Hitler and the Allies Misread the Strategic Realities of World War II, HarperCollins, 2004, pp. 2, 38.

- ↑ There are 58 ouvrages, 311 casemates, 78 shelters, 14 observatories and around 4,000 blockhouses on the North-West and 84 ouvrages, 41 casemates, 3 observatories and around 1,000 blockhouses on the South-West.

- ↑ Regan, Geoffrey. "The Guinness Book fo Military Blunders", 1991.

- ↑ Seramour, Michaël. "Histoire de la Ligne Maginot de 1945 à nos jours" (in French). Revue Historique des Armées. pp. 86–97. http://rha.revues.org/index1933.html. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ↑ Cain, Syd Not Forgetting James Bond 2005 Reynolds and Hearn

References

- Allcorn, William. The Maginot Line 1928-45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84176-646-1

- Kauffmann, J.E. and Kaufmann, H.W. Fortress France: The Maginot Line and French Defenses in World War II, 2006. ISBN 0-275-98345-5

Further reading

- Kauffmann, J.E. and Jurga, Robert M. Fortress Europe: European Fortifications of World War II, Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 0-306-81174-X

External links

- (French) The Maginot Line (French/English/German/Italian)

- (French) Fortress of Schoenenbourg, (French/English/German/Italian)

- (English) Maginot line (requires Flash)

- (English) Maginot Line at War, 1940

- (English) The U.S. Army vs. The Maginot Line by Bryan J. Dickerson

- (English) Maginot Line today

- (Czech) Armament of Maginot Line (Czech only)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||